by Amanda Rose Newton

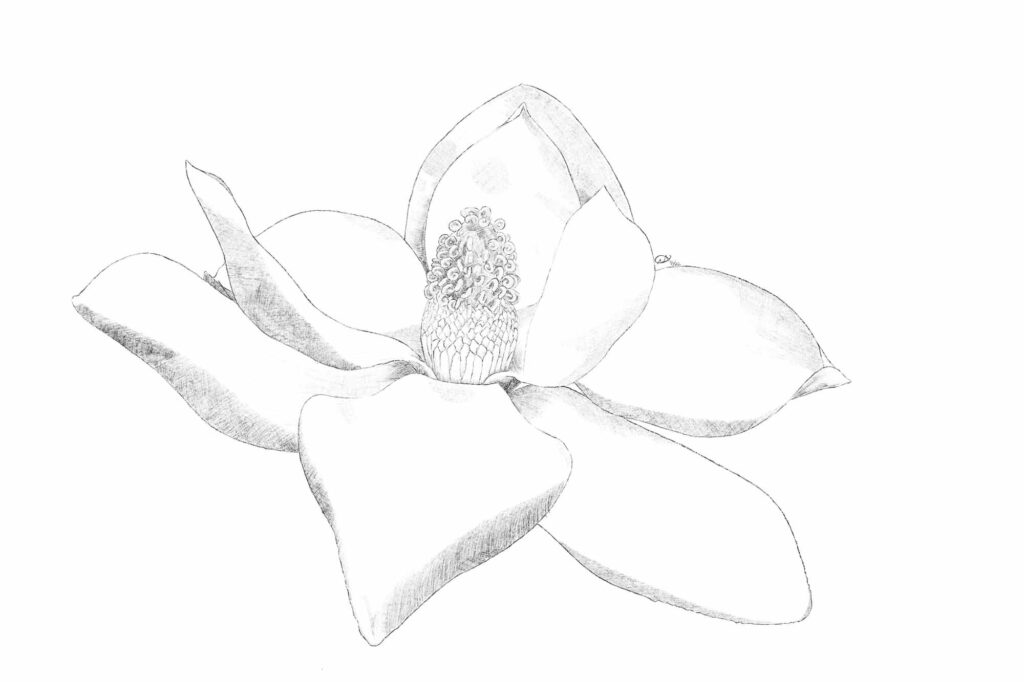

Botanical illustration, an art form as old as art itself, is once again gaining momentum in the modern world.

Before the days of photography, which is an arguably better way of viewing macroscopic details of plant anatomy, scientists and hobbyists relied heavily on detailed illustrated representations of living organisms.

While modern books rarely contain these works of art, their appeal prompts original works to sell for tens of thousands of dollars at auction houses worldwide.

Many of us plant lovers have long collected these works and likely have reproductions of famous illustrations hanging in our homes right now.

With in-tact publications becoming rarer with each change of the calendar year, preserving these beauties provides more than simply a lovely picture, but a window providing insight into the golden age of illustration.

The History of Plants as Artist’s Subjects

During the mid-first century, everyone from doctors to pharmacists to scientists required botanical illustrations to pepper publications and point out key distinctions and features they deemed useful.

The golden age of illustration occurred between the 15th and 17th centuries as exploration gave new reasons to depict the differences between species of botanical nature.

The invention of the printing press and the ability to use colored inks cemented the profession of botanical illustrators, making them sought after worldwide. As the profession picked up steam, many artists used metal plates in order to make copies of their illustrations in multiple volumes.

To this day, full-color pages in old scientific books are referred to as “plates”. It was one of the few professions at the time that offered opportunities for women, with many still being regarded as the best of the best.

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) is one of the earliest and most influential botanical artists of all time.

Fascinated by insects and secondly by plants, she is credited with being the first to illustrate the complete lifecycle of the butterfly as well as imagery of the caterpillar with its host plant of choice.

Her works appeared in many reference books and it’s not unusual for first-edition copies of her work to sell for half a million dollars or more.

Anne Pratt (1806-1893) rang in the Victorian age with more than 20 publications featuring her detailed illustrations of fruit and flowers.

Marianne North (1830-1890) picked up where Anne left off, traveling the world and documenting unique flora. In her lifetime, she painted more than 900 species of plants from 17 countries. Her works are still on display at the Kew Gardens in London.

Ernest Haeckel’s (1834-1919) works still receive top dollar today and chances are you have seen his illustrations before.

In addition to floral subjects, Haeckel’s ocean invertebrates and microscopic organism illustrations were instrumental in our early understanding. His legacy lives on as his works are constantly reproduced and used in everything from posters to oven mitts.

Modern Botanical Art

The profession refuses to die, even as photography reigns supreme. There is just something more personal about illustration that we are forever drawn to.

Major museums and botanical gardens still have working botanical illustrators, with many having additional training in graphic design.

Computer-enhanced illustrations allow us to still have the whimsical appearance of classic illustration that allows us to hone in on specific details needed for accurate identification.

For those interested, botanical illustration courses are still offered at major universities, botanical gardens, and even senior centers. Both drawing and green spaces are tied to positive mental health, so feel free to write this one off as needed for self-care.